Web and product designer Meagan Fisher has been building digital experiences for more than a decade—as a creative director at several New York–based startups, and partnering with clients such as Change.org, The Audubon Society, and Dribbble. She’s also an in-demand writer and speaker on issues related to user experience and web product design.

We recently sat down with Fisher to talk about her approach to design, being a designer who codes, and her love of owls.

Create: There are a lot of terms for what you do—how do you describe your work?

Meagan Fisher: I would describe myself as a web designer first—or digital designer is probably more accurate. We used to say web designer, but I design web interfaces and iPhone apps and desktop apps—and all kinds of things. So I think of myself as more of a digital designer. I also do front-end development, which makes me somewhat unique in the space, because most people either design or develop, but I do both.

Create: How has the work you do changed over time?

MF: I pride myself on being able to do a large breadth of design work. When I started out, my focus was on marketing sites—very content-heavy sites that didn’t lean as much on user experience. They were more about impactful visual design.

The reason I got into front-end development was that I wanted the sites I was building to have all the UX details I was designing—when you just hand a Photoshop file off to developers, details can get lost in translation. And then when responsive design came out, it was great because I could implement designs across a variety of devices myself, usually using markup but sometimes by working with a really great developer and designing in Photoshop. This was back in the day, of course—nowadays there's a broader range of tools.

Six years ago, I started doing iPhone app design, and this was kind of how I got into product design work. And that was really cool, because product design has a totally different set of challenges from marketing design. With product design, you're really thinking about user experience and how to make things as useful as possible, and that’s a lot thornier. It’s less about creating awesome visual impact and more about making the user flow as seamless as possible.

Since I started doing both, I’ve gone back and forth. I’ve done freelance on and off for my entire career and worked independently with a lot of great clients; I’ve also partnered with different agencies over the years as sort of an independent contractor.

And I’ve worked with a lot of small startups. I moved to New York in 2011, and I spent about five years working at different startups there. And sometimes I was one of just two or three designers on the team, which was really cool, because in those roles I got to do my front-end development work and marketing design and product design and user research and information architecture—it was a very rewarding chapter of my career, because it allowed me to become much more of an all-rounder. And now, just this year, I’ve gone back to doing freelance again.

Create: What kind of clients are you working with now?

MF: Most recently I’ve been working with Adobe, which has been awesome. And I just finished a project with the University of Pennsylvania that was really cool. Angela Duckworth, the author of the book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, is involved in a huge research project at the University of Pennsylvania that seeks to determine what helps people make lasting behavioral changes. As part of that, we designed a whole product and marketing experience to help people get into the study.

The first one we did was built around creating exercise habits, and we did that in partnership with 24 Hour Fitness. And she’s going to do another one around creating good financial habits, and she’s partnering with Bank of America for that one.

Then they’re also doing one where they work within the education system to figure out how to help people form good habits for things like studying…. It was a really cool project, because it’s in line with my personal values of helping people improve their lives and live the best life they can.

Fisher created these designs for a University of Pennsylvania research project that seeks to help people make lasting behavioral changes. You can learn more about this work in progress in this Medium post by Fisher.

Create: I saw something about that on your Dribbble profile—you say your focus is on making “products and services that honor their user’s humanity and help improve our world.” Do you feel like that’s one of the things that makes you unique?

MF: I don’t know if that makes me unique nowadays. I’d like to think that most designers think this way…. But yes, this is a big part of what I do. Over the years I’ve declined various projects where I couldn’t really see how it was ultimately going to improve the lives of anyone using the thing.

There’s a lot of stuff being created these days that, in one way or another, helps to spread misinformation, or is meant to waste the user’s time or otherwise exploit the user—and I never want my work to be about that. I want to design stuff that’s going to actively improve people’s lives, and I think that’s when technology is at its best.

I don’t know if you’ve read anything about dark UX patterns, but that’s definitely something people are talking about now—for instance, Facebook is full of examples of this, where the point of the design is to confuse or disorient the user, or to keep them continuously engaged, beyond what’s good for them or what they truly want. That’s the kind of stuff I avoid in my work.

As far as what makes my work unique—that’s the fact that I also code, because I’m thinking about how everything I create is eventually going to be implemented. I think having that knowledge helps me work with other developers. There’s an ongoing debate in the digital world about whether or not designers should know how to code, but I think it’s been a huge advantage in my career.

More screens from Fisher’s University of Pennsylvania project.

Create: What’s the argument for a designer not knowing how to code?

MF: Well, some designers find it intimidating, and as with any field, the argument is against becoming a jack of all trades but a master of none, so to speak. The argument is that any time you spend learning how to develop is time when you could be learning how to make great gradients or just, you know, focusing on the design side of your craft.

Also, I think some people would argue that if you have development limitations in mind, then you won’t come up with as many solutions in your design process, because your thinking is constrained. You’re limiting your imagination.

And those are all fair points. And it’s not that I build everything I design. If you work with a really great developer, they’re capable of thinking outside the box—and there are certainly developers who are masterful and go very far beyond what I can do.

It’s not my intention to be the best, but having even a little bit of that knowledge helps my communication with developers, and I believe it helps me create better work.

Create: Did you always want to go into this field?

MF: In a very roundabout way. I’ve always been interested in design, even when I was young. I’ve always been fascinated by technology and graphic design and art—that was my first passion, but I never really believed I could make a career doing that.

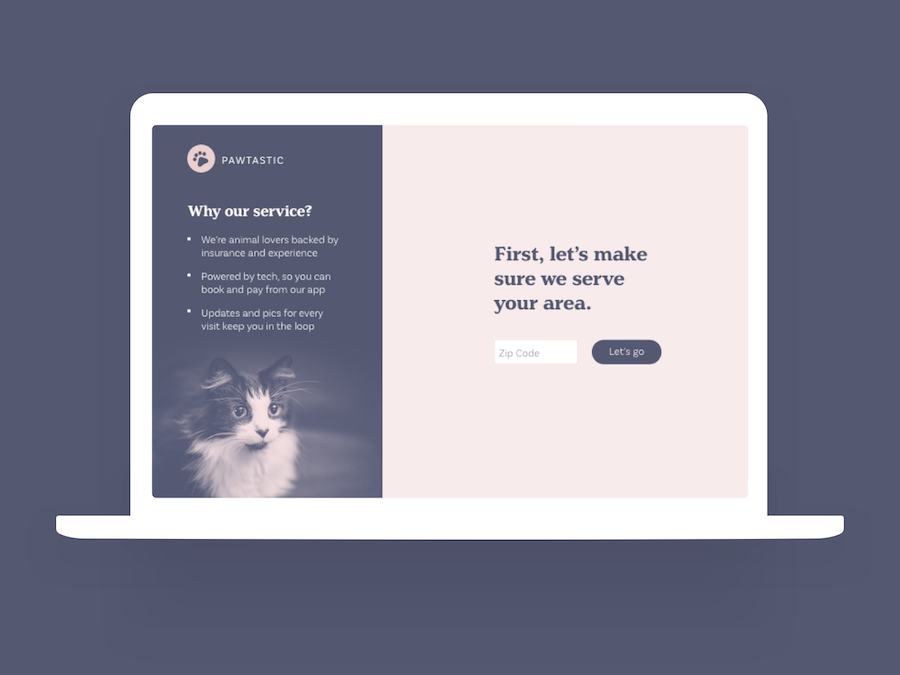

More screens from Fisher’s Pawtastic UI kit for Adobe XD.

So when I went to university, I studied English literature, and my plan was to be a teacher. But while I was at school, I was lucky enough to get a Mac laptop that had Flash on it. I worked at a hotel at the time, and I started playing around with Flash tutorials—and it really just took off from there. That rekindled the interest I’d always had in design. I started making free websites for friends. I had no idea what I was doing, but I loved playing around with Flash because it brought together all these different interests I’d always had.

It was funny because it just kind of started off as side hobby while I was getting my English degree and working in hotels. Then I got an internship at a startup—one that didn’t end up succeeding, unfortunately—where I was doing web design in Flash, so I decided to drop out of school and just do design full time.

Create: Web design or digital design is such a broad field, and is growing in such a way, that graphic designers and creatives in other disciplines often touch on digital design and UX in their work. What should people who don’t necessarily have training in that area keep in mind when they’re designing digital experiences? I know that’s a very broad question.

MF: The first thing that comes to mind is that I think a lot of graphic designers tend to create very beautiful work but don’t think about how real users will interact with the product.

And they often don’t think about the edge cases. A lot of the work you see on Behance or Dribbble will be really beautiful, but it only works for very specific scenarios. I think that’s the biggest mistake I see when I’m working with sort of junior graphic designers who are getting into digital design for the first time—they think about it like they’re designing a poster. But when you add dynamic content like real-world images or names or whatever it may be, the designs break. So that’s kind of the first thing: Make sure you’re working with real-world information and you’re testing your designs with real users.

This leads me to the second thing, which is to make sure you have a lot of access to your users and really understand who they are. When I was working at different startups, we might not have had a user research team, but we would all read the support tickets the users sent so we could see the struggles they were having with our product, or we would sit in on calls with the sales team to hear how users talked—things that would help us understand how people were using our products.

For designers, doing whatever you can to interact with your users in the real world and get a better sense of who they are—that is going to drastically improve your ability to design for them.

Fisher designed these screens as part of a marketing concept for a financial software company. Read more about the project in this Medium post by Fisher.

Create: That’s something I wanted to touch on with you: Digital design or interaction design is very much, it seems, a balance between science and creativity. How do you feel about that balance or maintain that balance? It seems like creating something beautiful and something very rigorously scientifically tested might almost be at odds, in some ways. Does that make sense or am I off base?

MF: It makes sense—it’s the question of how to innovate without pushing the innovation so far that what you’re creating is not really usable anymore.

Create: Right. You said it much better than I did.

MF: A good example is a website like Craigslist. Everyone knows how to use it. It’s perfectly intuitive and completely succeeds in doing what it needs to do, but it doesn’t necessarily innovate in terms of design.

With marketing design, there’s a lot more room to be creative and artful, because you’re trying to express a brand digitally as if it were a real entity. For instance, if you have a brand that’s meant to be very friendly and approachable, then you might get creative with bright colors or playful animations and come up with lots of different ways to express that.

With products, it’s a little bit different—that’s where you lean more toward the science of it, if you want to call it that: understanding user behavior and so on, because you’re not necessarily trying to be expressive in that case. You’re just trying to help the user achieve their goals easily and quickly.

But there’s always room for creativity. It’s funny: right before we started talking, I was doing my taxes, and not to plug them, but I use TurboTax, which is a very usable product that also has personality injected into it throughout. They use really warm language and have great illustrations—things like that. So I think you can look at the science of what creates the best experience, but then you can inject creativity into it with things like great micro copy or interesting illustrations or animations. In that way, the science is sort of the foundation, and the creativity is an enhancement.

Create: That makes great sense.

MF: I think that’s the best way to balance it. A lot of people want to design what’s beautiful first, I guess, and then try to make it work within the constraints of the science, and I think that it has to go the other way around.

Create: What are you excited about in your field these days?

MF: Well, it seems like there are two big topics that everyone is excited about right now.

One is the systematization of design—so rather than creating a unique interface for every element or a unique element for every aspect of your interface, it’s starting to come up with consistent symbols or repeating patterns within your work and establishing a set of best practices that people follow.

That’s a conversation we’re starting to have more, and it’s something I’m really excited about. I think having consistent elements helps the users know what they’re looking at and how to interact with things—it’s less mental strain on the user, and it’s also bringing the way designers think about product work and the way developers think about product work closer together.

In the past they’d often been at odds because designers want everything to be bespoke and beautiful, and developers want consistency and to limit the amount of code they’re creating.

So I think the fact that designers are starting to think about how they can create systems rather than totally unique interfaces is really exciting.

Second, you’re seeing people talk more and more about how animation and movement come into design. I was just joking that it’s come full circle, because when I started out with Flash, it was all about big impactful movements and crazy interactions and Flash loading screens where you basically had to sit through a feature film before you could get to the website. Then that all went out the door, and for a long time, everything was very static.

Then I think it was designers thinking about mobile device app designs, and those things really incorporated animation into the interaction…so that has led to everyone thinking about how to bring movement back into our work and how that can enhance the experience.

Create: Last question: You make your love of owls very plain, your site is called Owltastic—so what’s up with owls?

MF: That’s a fair question! The owl thing comes from a couple of different places. The biggest one is that for most of my career I’ve worked really late into the night. When I first started out, clients would be like, “Why are you emailing me at three o’clock in the morning?” Now I know a bit better and try to keep it to normal business hours, but I’m a night owl by nature.

Also, I love the way owls look. I actually just yesterday went to a bird sanctuary that’s about ten minutes from my house and got to hang out with a bunch of owls in person. And that was very exciting to me. Owls are fascinating creatures.

And then the other thing that’s kind of funny is when I left home for college, an owl moved into my parents’ backyard and would keep my dad up all night. It was really loud, and my dad said that he felt this owl had come to replace me in their lives. So that’s the third thing. I feel an affinity for owls. It’s a nighttime creature that makes a lot of noise, so—we have things in common.

April 17, 2018